13. Appendix: Scheme basics

Computing with functions

The \(\lambda\)-calculus formalizes the notion of computation using functions. Computation is performed in the \(\lambda\)-calculus by applying functions to arguments to compute results. Function application in Church looks like this:

(+ 1 1)Here we see the function + applied to two arguments: 1 and 1. Note that in Church the name of the function comes first and the parentheses go outside the function. This is sometimes called Polish notation. If you run this simple program above you will see the resulting value of this function application. Since + is a deterministic function you will always get the same return value if you run the program many times.

Some functions in Church can take an arbitrary number of arguments. For instance, + can take just 1 argument:

(+ 3.1)or 2 arguments:

(+ 3.1 2.7)or 15 arguments:

(+ 3.1 2.7 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13)Such functions are called “variadic” functions.

Building More Complex Programs

A Church program is syntactically composed of nested expressions. Roughly speaking an expression is either a simple value, or anything between parentheses (). In a deterministic LISP, like Scheme, all expressions without free variables have a single fixed value which is computed by a process known as evaluation. For example, consider the following more complex expression:

(and true (or true false))This expression has an operator, the logical function and, and arguments, true and the subexpression which is itself an application of or. When reasoning about evaluation, it is best to think of evaluating the subexpressions first, then applying the function to the return values of its arguments. In this example or is first applied to true and false, returning true, then and is applied to true and the subexpression’s return value, again returning true.

As a slightly more complex example, consider:

;this line is a comment

(if

(= 1 2) ;the condition of "if"

100 ;the consequent ("then")

(or true false) ;the alternate ("else")

)This expression is composed of an if conditional that evaluates the first expression (a test here of whether 1 equals 2) then evaluates the second expression if the first is true or otherwise evaluates the third expression. The operator if is strictly not a function, because it does not evaluate all of its arguments, but instead short-circuits evaluating only the second or third. It has a value like any other function. (We have also used comments here: anything after a semicolon is ignored when evaluating.)

Note the particular indentation style used above (called ‘’pretty-printing’’). To clarify the structure of a function call, the arguments can split up across different lines, but keeping them vertically aligned helps readability:

(+ (* 3

(+ (* 2 4)

(+ 3 5)))

(+ (- 10 7)

6))The online editor will automatically pretty-print for you. You can re-indent according to this style by selecting some lines and pressing the TAB key.

We often want to name objects in our programs so that they can be reused. This can be done with the define statement. define looks like this:

(define variable-name expression)variable-name is a symbol that is bound to the value that expression evaluates to. When variables themselves are evaluated they return the value that they have been bound to:

(define some-variable 10) ;assign the value 10 to the variable some-variable

some-variable ;when this is evaluated it looks up and returns the value 10Lists and symbols

There are several special kinds of values in Church. One kind of special value is a list: a sequence of other values. Lists are a fundamental data structure in LISP-like languages. In fact, a Church program is just a list—the list of expressions comprising the program. Lists can be built using the list function and manipulated using functions such as first (get the first element in a list) and rest (get the rest of the list after the first element).

(first ;get the first element of

(rest ;get non-first elements of

(list "this" "is" "a" "list"))) ;build a list!Experiment with different combinations of these functions. What happens when you apply list to the result of list? (In this program we have used another kind of special value: a string, which is anything between double-quotes.)

Sometimes we wish to treat a piece of Church code “literally”, that is, to view it as a value rather than an expression. We can do this using a special quote operation (which can also be written with a single quote: (quote ...) is the same as '...):

(define quoted-value '(1 2 3))

(first quoted-value)What is the value of quoted-value? What happens if you remove the quote? Why?

The quote operator is not the same as the list function. Everything inside a quote is taken literally, with no evaluation, while the arguments to list are first evaluated and then made into a list. Compare the value of:

(list (+ 1 2) 2)to the value of:

'( (+ 1 2) 3)If we quote the name of a variable, what we get back is a symbol: a value which is the literal variable, rather than the value it is bound to. A symbol is just an identifier; it will be equal to itself, but to no other symbol:

(define foo 1)

(list

;a symbol is equal to itself

(equal? 'foo 'foo)

;but not equal to any other symbol

(equal? 'foo 'bar)

;or value

(equal? 'foo 2)

;even the value that it is bound to as a variable

(equal? 'foo foo))The ability to make new symbols as needed is a crucial feature in building models that reason over unbounded worlds, as we’ll see below.

Some useful functions on lists:

(length lst)returns the number of items in a list.(null? lst)returns true if a list is empty, false otherwise(first lst)returns the first item oflst, while(rest lst)returns everything but the first item oflst. For convenience,second,third,fourth,fifth,sixth, andseventhare also defined.(append lst1 lst2 ...)will put lists together:(append '(1 2 3) '(4 5) '(6 7))Note that append is a variadic function.

Lists can contain lists, e.g.:

'( 1 2 3 (4.1 4.2 4.3) 5)This nesting property is useful because it allows us to represent hierarchical structure. Note that calling length on the above function would return 5 (not 7) - length only counts the top-level items. You can remove all the nesting from a list using the flatten function (so (length (flatten '( 1 2 3 (4.1 4.2 4.3) 5))) would return 7).

Sometimes, you’ll want to call a variadic function, but you don’t know how many arguments you will have in advance. In these cases, you can keep around a list of arguments and use apply to call the variadic function on that list. In other words, this:

(+ 1 2 3 4 5 6 7)

is equivalent to this:

(apply + '(1 2 3 4 5 6 7))

Building Functions: lambda

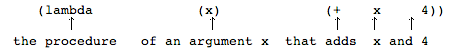

The power of lambda calculus as a model of computation comes from the ability to make new functions. To do so, we use the lambda primitive. For example, we can construct a function that doubles any number it is applied to:

(define double (lambda (x) (+ x x)))

(double 3)The general form of a lambda expression is: (lambda arguments body) The first sub-expression of the lambda, the arguments, is a list of symbols that tells us what the inputs to the function will be called; the second sub-expression, the body, tells us what to do with these inputs. The value which results from a lambda expression is called a compound procedure. When a compound procedure is applied to input values (e.g. when double was applied to 3) we imagine identifying (also called binding) the argument variables with these inputs, then evaluating the body. As another simple example, consider this function:

In lambda calculus we can build procedures that manipulate any kind of value—even other procedures. Here we define a function twice which takes a procedure and returns a new procedure that applies the original twice:

(define double (lambda (x) (+ x x)))

(define twice (lambda (f) (lambda (x) (f (f x)))))

((twice double) 3)This ability to make higher-order functions is what makes the lambda calculus a universal model of computation.

Since we often want to assign names to functions, (define (foo x) ...) is short (“syntactic sugar”) for (define foo (lambda (x) ...)). For example we could have written the previous example:

(define (double x) (+ x x))

(define (twice f) (lambda (x) (f (f x))))

((twice double) 3)Useful Syntax

Scheme comes with some syntax to make it more pleasant to build programs. (All of this syntax, however, can be quickly converted to the basic syntax, such as lambda and function application.) The let construct is a way to bind values to names (much like define), and it can be used as an ordinary expression:

(let ((a (+ 1 1)))

(+ a 1))The case construct is an alternative to writing a long list of if statement. For instance:

(define a 1)

(case a

((1) "hi")

((2) "bye")

(else "error"))This is equivalent to:

(define a 1)

(if (equal? a 1)

"hi"

(if (equal? a 2)

"bye"

"error"))Higher-Order Functions

Higher-order functions can be used to represent common patterns of computation. Several such higher-order functions are provided in Church.

map is a higher-order function that takes a procedure and applies it to each element of a list. For instance we could use map to test whether each element of a list of numbers is greater than zero:

(map (lambda (x) (> x 0)) '(1 -3 2 0))The map higher-order function can also be used to map a function of more than one argument over multiple lists, element by element. For example, here is the MATLAB “dot-star” function (or “.*”) written using map:

(define dot-star (lambda (v1 v2) (map * v1 v2)))

(dot-star '(1 2 3) '(4 5 6))The higher-order function apply, takes a procedure and applies to a list as if the list were direct arguments to the procedure. The standard functions sum and product can be easily defined in terms of (apply + ...) and (apply * ...), respectively. To illustrate this:

(define my-list '(3 5 2047))

(list "These numbers should all be equal:" (sum my-list) (apply + my-list) (+ 3 5 2047))Exercises

In Church you call functions like this:

(function arg1 arg2 arg3). For example,(+ 1 2)would return 3. Try running it:; comments are preceded by semicolons (+ 1 2)Write the computation \(3 \times 4\) in Church (

*is the multiplication function).Write the computation \(3 \times (4 + 6)\) in Church (make sure the result is 30).

Write the computation \(3 \times [4+ (6/7)]\) in Church (make sure the result is \(\approx\) 14.57)

Write the computation \(3 \times [4+ (6/7)^2]\) in Church. The Church function

(expt a b)will give you \(a^b\). Make sure the result is \(\approx\) 14.20.Convert this Church expression into an arithmetic expression:

(/ 1 (+ 4 5))Convert this Church expression to an arithmetic expression:

(/ 1 (* (+ 2 3) (- 4 6)))Why doesn’t this code work?

(4 + 6)

Defining variables and functions:

Write a function \(f(x, y) = (x + y)^{x - y}\) and use it to compute \(f(5,3)\). Fill in the blanks for defining \(f\) using the short syntax:

(define (f ...) ...) (f 5 3)Now fill in the blank for defining \(f\) using the long syntax; make sure that you get the same answer for \(f(5,3)\).

(define f (lambda (...) ... )) (f 5 3)Below, we have already defined \(h(x,y) = x + 2y\). Using the short syntax, write a function \(g(x, y, z) = x - y \times z\) and use it to compute \(g(1, 4, h(6,3))\).

(define (h x y) (+ x (* 2 y)))Now define \(g\) using the long syntax; make sure that you get the same answer for \(g(1, 4, h(6, 3))\)

(define (h x y) (+ x (* 2 y)))The

(if <condition> <true-clause> <false-clause> )special form is used for if-else statements. For instance, it’s used below to define a function that returnsyesif the first argument is bigger than the second andnootherwise.(define (bigger? a b) (if (> a b) 'yes 'no)) (bigger? 3 4)In Church, the Boolean values true and false are represented by

#tand#f(so(> 5 1)would return#tand(> 5 7)would return#f).What does the function below do?

(define (f x) (if (> x 5) 'Z (if (> x 2) 'R 'M)))Scheme and Church are functional programming languages, so functions have a special place in these languages. Speaking very loosely, if you think of variables as nouns and functions as verbs, functional programming languages blur the noun-verb distinction. A consequence of this is that you can treat functions like regular old values. For instance, in the function below, there are three arguments:

thing1,thing2, andthing3.thing1is assumed to be a function and it gets applied tothing2andthing3:(define (use-thing1-on-other-things thing1 thing2 thing3) (thing1 thing2 thing3)) (use-thing1-on-other-things * 3 4)Write a function,

f, that takes three arguments,g,x, andy. Assume thatgis a function of two variables and definefso that it returns'yesif \(g(x,y) > x + y\), otherwise'no. Use it to compute \(f(\times, 2.6, 1.2)\).(define (f g x y) ...)In D we defined

fas a function that takes in a function as one of its arguments. Here, we are going to define a different sort of function, one that takes in normal values as arguments but returns a function.(define (bigger-than-factory num) (lambda (x) (> x num)))You can think of this function as a “factory”. You hand this factory a number,

num, and the factory hands you back a machine. This machine is itself a function that takes an number,x, and tells you whetherxis larger than num.Without running any code, compute

((bigger-than-factory 5) 4)and((bigger-than-factory -1) 7).The functions we’ve defined in parts D and E are called “higher order functions”. A function \(f\) is a higher order function if it takes other functions as input or if it outputs a function.

What does this function do?

(define (Q f g) (lambda (x y) (> (f x y) (g x y))))

Two important data structures in Scheme/Church are pairs and lists. A pair is just a combination of two things, a head and a tail. In Church, if you already have

xandy, you can combine them into a pair by calling(pair x y):(define x 3) (define y 9) (pair x y)Observe that this code returns the result

(3 . 9)- you can recognize a pair by the dot in the middle.Lists are built out of pairs. In particular, a list is just a sequence of nested pairs whose last element is

'()(pronounced “null”). So, this would be the list containing'a,'6,'b,'c,7, and'd:(pair 'a (pair '6 (pair 'b (pair 'c (pair 7 (pair 'd '()))))))Of course, stringing together a bunch of

pairstatements gets tedious, so there is a shorthand - thelistfunction:(list 'a 6 'b 'c 7 'd)An alternate way of specifying the above list is using the quote syntax:

'(a 6 b c 7 d)The following code tries to define a list but gives an error instead. Why?

(3 4 7 8)Using

listsyntax, write a list of the even numbers between 0 and 10 inclusive.Using quote syntax, write a list of the odd numbers between 1 and 9 inclusive.

Without running any code, guess the result of each expression below. Some of these expressions have intentional errors—see if you can spot them.

(pair 1 (pair 'foo (pair 'bar '() ))(pair (1 2))(length '(1 2 3 (4 5 6) 7))(append '(1 2 3) '(4 5) '( 7 (8 9) ))(length (apple pear banana))(equal? (pair 'a (pair 'b (pair 'c '() ))) (append '(a b) '(c)))(equal? (pair 'd (pair 'e (pair 'f 'g))) '(d e f g))Check your guesses by actually running the code. If you made any mistakes, explain why your initial guess was incorrect.

;; run code here

Two common patterns for working with lists are called

mapandfold(fold is also sometimes calledreduce).Map takes two arguments, a function,

f, and a list,(list a b c ...), and returns a list withfapplied to every item of the list:(list (f a) (f b) (f c) ...). In the example below, we mapsquare(which squares numbers) over the first five natural numbers:(define (square x) (* x x)) (map square '(1 2 3 4 5))Fold takes three arguments, a function,

f, an initial value,i, and a list,(list a b c ...), and returns(f ... (f c (f b (f a i)))). In the example below, we define a function that computes the product of a list:(define (my-product lst) (fold ;; function (lambda (list-item cumulative-value) (* list-item cumulative-value)) ;; initial value 1 ;; list lst)) (my-product '(1 2 3 4 5))Note the use of the “anonymous” function here—we don’t care about using this function outside the context of the fold, so we don’t bother giving it a name with

define.Write

my-sum-squaresusingfold. This function should take in a list of numbers and return the sum of the squares of all those numbers. Use it on the list'(1 2 3 4 5)(define (square x) (* x x)) (define (my-sum-squares lst) ...) (my-sum-squares '(1 2 3 4 5))Write

my-sum-squareswithout usingfold—instead usemapandapply:(define (square x) (* x x)) (define (my-sum-squares lst) ...) (my-sum-squares '(1 2 3 4 5))

One benefit of functional programming languages is that they make it possible to elegantly and concisely write down interesting programs that would be complicated and ugly to express in non-functional languages (if you have some time, it is well worth understanding the change counting example from SICP). Elegance and concision usually derive from recursion, i.e., expressing a problem in terms of a smaller subproblem.

Here is a very simple recursive function, one that computes the length of a list:

(define (my-length lst) (if (null? lst) 0 (+ 1 (my-length (rest lst))))) (my-length '(a b c d e))How does

my-lengthwork?Below,

my-maxis intended to be a recursive function that returns the largest item in a list. Finish writing it and use it to compute the largest item in'(1 2 3 6 7 4 2 9 8 -5 0 12 3); returns the larger of a and b. (define (bigger a b) (if (> a b) a b)) (define (my-max lst) (if (= (length lst) 1) (first lst) ...)) (my-max '(1 2 3 6 7 4 2 9 8 -5 0 12 3))Write a version of

my-maxusingfold.(define (bigger a b) (if (> a b) a b)) (define (my-max lst) (fold ...)) (my-max '(1 2 3 6 7 4 2 9 8 -5 0 12 3))