6. Inference about inference

The query operator is an ordinary Church function, in the sense that it can occur anywhere that any other function can occur. In particular, we can construct a query with another query inside of it: this represents hypothetical inference about a hypothetical inference. Nested queries are particularly useful in modeling social cognition: reasoning about another agent, who is herself reasoning.

(There are some implementation-specific restrictions on nesting queries: the rejection-query operator can always be nested, while nesting mh-query requires special syntax.)

Prelude: Thinking About Assembly Lines

Imagine a factory where the widget-maker makes a stream of widgets, and the widget-tester removes the faulty ones. You don’t know what tolerance the widget tester is set to, and wish to infer it. We can represent this as:

(define (sample)

(rejection-query

;;this machine makes a widget -- which we'll just represent with a real number:

(define (widget-maker) (multinomial '(.2 .3 .4 .5 .6 .7 .8) '(.05 .1 .2 .3 .2 .1 .05)))

;;this machine tests widgets as they come out of the widget-maker, letting

;; through only those that pass threshold:

(define (next-good-widget)

(define widget (widget-maker))

(if (> widget threshold)

widget

(next-good-widget)))

;;but we don't know what threshold the widget tester is set to:

(define threshold (multinomial '(.3 .4 .5 .6 .7) '(.1 .2 .4 .2 .1)))

;;what is the threshold?

threshold

;;if we see this sequence of good widgets:

(equal? (repeat 3 next-good-widget)

'(0.6 0.7 0.8))))

(hist (repeat 20 sample))But notice that the definition of next-good-widget is exactly like the definition of rejection sampling! We can re-write this as a nested-query model:

(define (sample)

(rejection-query

;;this machine makes a widget -- which we'll just represent with a real number:

(define (widget-maker) (multinomial '(.2 .3 .4 .5 .6 .7 .8) '(.05 .1 .2 .3 .2 .1 .05)))

;;this machine tests widgets as they come out of the widget-maker, letting

;; through only those that pass threshold:

(define (next-good-widget)

(rejection-query

(define widget (widget-maker))

widget

(> widget threshold)))

;;but we don't know what threshold the widget tester is set to:

(define threshold (multinomial '(.3 .4 .5 .6 .7) '(.1 .2 .4 .2 .1)))

;;what is the threshold?

threshold

;;if we see this sequence of good widgets:

(equal? (repeat 3 next-good-widget)

'(0.6 0.7 0.8))))

(hist (repeat 20 sample))Rather than thinking about the details inside the widget tester, we are now abstracting to represent that the machine correctly chooses a good widget (by some means).

Social Cognition

How can we capture our intuitive theory of other people? Central to our understanding is the principle of rationality: an agent tends to choose actions that she expects to lead to outcomes that satisfy her goals. (This is a slight restatement of the principle as discussed in C. L. Baker, Saxe, & Tenenbaum (2009), building on earlier work by Dennett (1989), among others.) We can represent this in Church by a query—an agent infers an action which will lead to their goal being satisfied:

(define (choose-action goal? transition state)

(query

(define action (action-prior))

action

(goal? (transition state action))))The function transition describes the outcome of taking a particular action in a particular state, the predicate goal? determines whether or not a state accomplishes the goal, the input state represents the current state of the world. The function action-prior used within choose-action represents an a-priori tendency towards certain actions.

For instance, imagine that Sally walks up to a vending machine wishing to have a cookie. Imagine also that we know the mapping between buttons (potential actions) and foods (outcomes). We can then predict Sally’s action:

(define (choose-action goal? transition state)

(rejection-query

(define action (action-prior))

action

(goal? (transition state action))))

(define (action-prior) (uniform-draw '(a b)))

(define (vending-machine state action)

(case action

(('a) 'bagel)

(('b) 'cookie)

(else 'nothing)))

(define (have-cookie? object) (equal? object 'cookie))

(define (sample)

(choose-action have-cookie? vending-machine 'state))

(hist (repeat 100 sample))We see, unsurprisingly, that if Sally wants a cookie, she will always press button b. (In defining the vending machine we have used a case statement instead of a long set of ifs.) In a world that is not quite so deterministic Sally’s actions will be more stochastic:

;;;fold: choose-action

(define (choose-action goal? transition state)

(rejection-query

(define action (action-prior))

action

(goal? (transition state action))))

;;;

(define (action-prior) (uniform-draw '(a b)))

(define (vending-machine state action)

(case action

(('a) (multinomial '(bagel cookie) '(0.9 0.1)))

(('b) (multinomial '(bagel cookie) '(0.1 0.9)))

(else 'nothing)))

(define (have-cookie? object) (equal? object 'cookie))

(define (sample)

(choose-action have-cookie? vending-machine 'state))

(hist (repeat 100 sample))Technically, this method of making a choices is not optimal, but rather it is soft-max optimal (also known as following the “Boltzmann policy”).

Goal Inference

Now imagine that we don’t know Sally’s goal (which food she wants), but we observe her pressing button b. We can use a query to infer her goal (this is sometimes called “inverse planning”, since the outer query “inverts” the query inside choose-action).

;;;fold: choose-action

(define (choose-action goal? transition state)

(rejection-query

(define action (action-prior))

action

(goal? (transition state action))))

;;;

(define (action-prior) (uniform-draw '(a b)))

(define (vending-machine state action)

(case action

(('a) (multinomial '(bagel cookie) '(0.9 0.1)))

(('b) (multinomial '(bagel cookie) '(0.1 0.9)))

(else 'nothing)))

(define (sample)

(rejection-query

(define goal-food (uniform-draw '(bagel cookie)))

(define goal? (lambda (outcome) (equal? outcome goal-food)))

goal-food

(equal? (choose-action goal? vending-machine 'state) 'b)))

(hist (repeat 100 sample))Now let’s imagine a more ambiguous case: button b is “broken” and will (uniformly) randomly result in a food from the machine. If we see Sally press button b, what goal is she most likely to have?

;;;fold: choose-action

(define (choose-action goal? transition state)

(rejection-query

(define action (action-prior))

action

(goal? (transition state action))))

;;;

(define (action-prior) (uniform-draw '(a b)))

(define (vending-machine state action)

(case action

(('a) (multinomial '(bagel cookie) '(0.9 0.1)))

(('b) (multinomial '(bagel cookie) '(0.5 0.5)))

(else 'nothing)))

(define (sample)

(rejection-query

(define goal-food (uniform-draw '(bagel cookie)))

(define goal? (lambda (outcome) (equal? outcome goal-food)))

goal-food

(equal? (choose-action goal? vending-machine 'state) 'b)))

(hist (repeat 100 sample)) Despite the fact that button b is equally likely to result in either bagel or cookie, we have inferred that sally probably wants a cookie. This is a result of the inference implicitly taking into account the counterfactual alternatives: if Sally had wanted a bagel, she would have likely pressed button a. The inner query takes these alternatives into account, adjusting the probability of the observed action based on alternative goals.

Preferences

If we have some prior knowledge about Sally’s preferences (which goals she is likely to have) we can incorporate this immediately into the prior over goals (which above was uniform).

A more interesting situation is when we believe that Sally has some preferences, but we don’t know what they are. We capture this by adding a higher level prior (a uniform) over preferences. Using this we can learn about Sally’s preferences from her actions: after seeing Sally press button b several times, what will we expect her to want the next time?

;;;fold: choose-action

(define (choose-action goal? transition state)

(rejection-query

(define action (action-prior))

action

(goal? (transition state action))))

;;;

(define (action-prior) (uniform-draw '(a b)))

(define (vending-machine state action)

(case action

(('a) (multinomial '(bagel cookie) '(0.9 0.1)))

(('b) (multinomial '(bagel cookie) '(0.1 0.9)))

(else 'nothing)))

(define (sample)

(rejection-query

(define food-preferences (uniform 0 1))

(define (goal-food-prior) (if (flip food-preferences) 'bagel 'cookie))

(define (make-goal food)

(lambda (outcome) (equal? outcome food)))

(goal-food-prior)

(and (equal? (choose-action (make-goal (goal-food-prior)) vending-machine 'state) 'b)

(equal? (choose-action (make-goal (goal-food-prior)) vending-machine 'state) 'b)

(equal? (choose-action (make-goal (goal-food-prior)) vending-machine 'state) 'b))))

(hist (repeat 100 sample)) Try varying the amount and kind of evidence. For instance, if Sally one time says “I want a cookie” (so you have directly observed her goal that time) how much evidence does that give you about her preferences, relative to observing her actions?

In the above preference inference, it is extremely important that sally could have taken a different action if she had a different preference (i.e. she could have pressed button a if she preferred to have a bagel). In the program below we have set up a situation in which both actions lead to cookie most of the time:

;;;fold: choose-action

(define (choose-action goal? transition state)

(rejection-query

(define action (action-prior))

action

(goal? (transition state action))))

;;;

(define (action-prior) (uniform-draw '(a b)))

(define (vending-machine state action)

(case action

(('a) (multinomial '(bagel cookie) '(0.1 0.9)))

(('b) (multinomial '(bagel cookie) '(0.1 0.9)))

(else 'nothing)))

(define (sample)

(rejection-query

(define food-preferences (uniform 0 1))

(define (goal-food-prior) (if (flip food-preferences) 'bagel 'cookie))

(define (make-goal food)

(lambda (outcome) (equal? outcome food)))

(goal-food-prior)

(and (equal? (choose-action (make-goal (goal-food-prior)) vending-machine 'state) 'b)

(equal? (choose-action (make-goal (goal-food-prior)) vending-machine 'state) 'b)

(equal? (choose-action (make-goal (goal-food-prior)) vending-machine 'state) 'b))))

(hist (repeat 100 sample)) Now we can draw no conclusion about Sally’s preferences. Try varying the machine probabilities, how does the preference inference change? This effect, that the strength of a preference inference depends on the context of alternative actions, has been demonstrated in young infants by Kushnir, Xu, & Wellman (2010).

Epistemic States

In the above models of goal and preference inference, we have assumed that the structure of the world (both the operation of the vending machine and the, irrelevant, initial state) were common knowledge—they were non-random constructs used by both the agent (Sally) selecting actions and the observer interpreting these actions. What if we (the observer) don’t know how exactly the vending machine works, but think that however it works Sally knows? We can capture this by placing uncertainty on the vending machine, inside the overall query but “outside” of Sally’s inference:

;;;fold: choose-action

(define (choose-action goal? transition state)

(rejection-query

(define action (action-prior))

action

(goal? (transition state action))))

;;;

(define (action-prior) (uniform-draw '(a b)))

(define (make-vending-machine a-effects b-effects)

(lambda (state action)

(case action

(('a) (multinomial '(bagel cookie) a-effects))

(('b) (multinomial '(bagel cookie) b-effects))

(else 'nothing))))

(define (sample)

(rejection-query

(define a-effects (dirichlet '(1 1)))

(define b-effects (dirichlet '(1 1)))

(define vending-machine (make-vending-machine a-effects b-effects))

(define goal-food (uniform-draw '(bagel cookie)))

(define goal? (lambda (outcome) (equal? outcome goal-food)))

(second b-effects)

(and (equal? goal-food 'cookie)

(equal? (choose-action goal? vending-machine 'state) 'b) )))

(define samples (repeat 500 sample))

(display (list "mean:" (mean samples)))

(hist samples "Probability that b gives cookie")Here we have conditioned on Sally wanting the cookie and Sally choosing to press button b. Thus, we have no direct evidence of the effects of pressing the buttons on the machine. What happens if you condition instead on the action and outcome, but not the intentional choice of this outcome (that is, change the condition to (equal? (vending-machine 'state 'b) 'cookie))?

Now imagine a vending machine that has only one button, but it can be pressed many times. We don’t know what the machine will do in response to a given button sequence. We do know that pressing more buttons is less a priori likely.

;;;fold: choose-action

(define (choose-action goal? transition state)

(rejection-query

(define action (action-prior))

action

(goal? (transition state action))))

;;;

(define (action-prior) (if (flip 0.7) '(a) (pair 'a (action-prior))))

(define (sample)

(rejection-query

(define buttons->outcome-probs (mem (lambda (buttons) (dirichlet '(1 1)))))

(define (vending-machine state action)

(multinomial '(bagel cookie) (buttons->outcome-probs action)))

(define goal-food (uniform-draw '(bagel cookie)))

(define goal? (lambda (outcome) (equal? outcome goal-food)))

(list (second (buttons->outcome-probs '(a a)))

(second (buttons->outcome-probs '(a))))

(and (equal? goal-food 'cookie)

(equal? (choose-action goal? vending-machine 'state) '(a a)) )

))

(define samples (repeat 500 sample))

(hist (map first samples) "Probability that (a a) gives cookie")

(hist (map second samples) "Probability that (a) gives cookie")Compare the inferences that result if Sally presses the button twice to those if she only presses the button once. Why can we draw much stronger inferences about the machine when Sally chooses to press the button twice? When Sally does press the button twice, she could have done the “easier” (or rather, a priori more likely) action of pressing the button just once. Since she doesn’t, a single press must have been unlikely to result in a cookie. This is an example of the principle of efficiency—all other things being equal, an agent will take the actions that require least effort (and hence, when an agent expends more effort all other things must not be equal). Here, Sally has an infinite space of possible actions but, because these actions are constructed by a recursive generative process, simpler actions are a priori more likely.

In these examples we have seen two important assumptions combining to allow us to infer something about the world from the indirect evidence of an agents actions. The first assumption is the principle of rational action, the second is an assumption of knowledgeability—we assumed that Sally knows how the machine works, though we don’t. Thus inference about inference, can be a powerful way to learn what others already know, by observing their actions. (This example was inspired by Goodman, Baker, & Tenenbaum (2009))

Joint inference about beliefs and desires

In social cognition, we often make joint inferences about two kinds of mental states: agents’ beliefs about the world and their desires, goals or preferences. We can see an example of such a joint inference in the vending machine scenario. Suppose we condition on two observations: that Sally presses the button twice, and that this results in a cookie. Then, assuming that she knows how the machine works, we jointly infer that she wanted a cookie, that pressing the button twice is likely to give a cookie, and that pressing the button once is unlikely to give a cookie.

;;;fold: choose-action

(define (choose-action goal? transition state)

(rejection-query

(define action (action-prior))

action

(goal? (transition state action))))

;;;

(define (action-prior) (if (flip 0.7) '(a) (pair 'a (action-prior))))

(define (sample)

(rejection-query

(define buttons->outcome-probs (mem (lambda (buttons) (dirichlet '(1 1)))))

(define (vending-machine state action)

(multinomial '(bagel cookie) (buttons->outcome-probs action)))

(define goal-food (uniform-draw '(bagel cookie)))

(define goal? (lambda (outcome) (equal? outcome goal-food)))

(list (second (buttons->outcome-probs '(a a)))

(second (buttons->outcome-probs '(a)))

goal-food)

(and (equal? (vending-machine 'state '(a a)) 'cookie)

(equal? (choose-action goal? vending-machine 'state) '(a a)) )

))

(define samples (repeat 500 sample))

(hist (map first samples) "Probability that (a a) gives cookie")

(hist (map second samples) "Probability that (a) gives cookie")

(hist (map third samples) "Goal probabilities")Notice the U-shaped distribution for the effect of pressing the button just once. Without any direct evidence about what happens when the button is pressed just once, we can infer that it probably won’t give a cookie—because her goal is likely to have been a cookie but she didn’t press the button just once—but there is a small chance that her goal was actually not to get a cookie, in which case pressing the button once could result in a cookie. This very complex (and hard to describe!) inference comes naturally from joint inference of goals and knowledge.

Communication and Language

A Communication Game

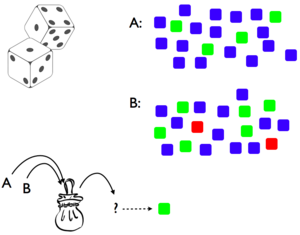

Imagine playing the following two-player game. On each round the “teacher” pulls a die from a bag of weighted dice, and has to communicate to the “learner” which die it is (both players are familiar with the dice and their weights). However, the teacher may only communicate by giving the learner examples: showing them faces of the die.

We can formalize the inference of the teacher in choosing the examples to give by assuming that the goal of the teacher is to successfully teach the hypothesis – that is, to choose examples such that the learner will infer the intended hypothesis (throughout this section we simplify the code by specializing to the situation at hand, rather than using the more general choose-action function introduced above):

(define (teacher die)

(query

(define side (side-prior))

side

(equal? die (learner side))))The goal of the learner is to infer the correct hypothesis, given that the teacher chose to give these examples:

(define (learner side)

(query

(define die (die-prior))

die

(equal? side (teacher die))))This pair of mutually recursive functions represents a teacher choosing examples or a learner inferring a hypothesis, each thinking about the other. However, notice that this recursion will never halt—it will be an unending chain of “I think that you think that I think that…”. To avoid this infinite recursion say that eventually the learner will just assume that the teacher rolled the die and showed the side that came up (rather than reasoning about the teacher choosing a side):

(define (teacher die depth)

(query

(define side (side-prior))

side

(equal? die (learner side depth))))

(define (learner side depth)

(query

(define die (die-prior))

die

(if (= depth 0)

(equal? side (roll die))

(equal? side (teacher die (- depth 1))))))To make this concrete, assume that there are two dice, A and B, which each have three sides (red, green, blue) that have weights like so:

Which hypothesis will the learner infer if the teacher shows the green side?

(define (teacher die depth)

(rejection-query

(define side (side-prior))

side

(equal? die (learner side depth))))

(define (learner side depth)

(rejection-query

(define die (die-prior))

die

(if (= depth 0)

(equal? side (roll die))

(equal? side (teacher die (- depth 1))))))

(define (die->probs die)

(case die

(('A) '(0.0 0.2 0.8))

(('B) '(0.1 0.3 0.6))

(else 'uhoh)))

(define (side-prior) (uniform-draw '(red green blue)))

(define (die-prior) (if (flip) 'A 'B))

(define (roll die) (multinomial '(red green blue) (die->probs die)))

(define depth 0)

(learner 'green depth)If we run this with recursion depth 0—that is a learner that does probabilistic inference without thinking about the teacher thinking—we find the learner infers hypothesis B most of the time (about 60% of the time). This is the same as using the “strong sampling” assumption: the learner infers B because B is more likely to have landed on side 2. However, if we increase the recursion depth we find this reverses: the learner infers B only about 40% of the time. Now die A becomes the better inference, because “if the teacher had meant to communicate B, they would have shown the red side because that can never come from A.”

This model, has been proposed by Shafto, Goodman, & Frank (2012) as a model of natural pedagogy. They describe several experimental tests of this model in the setting of simple “teaching games,” showing that people make inferences as above when they think the examples come from a helpful teacher, but not otherwise.

Communicating with Words

Unlike the situation above, in which concrete examples were given from teacher to student, words in natural language denote more abstract concepts. However, we can use almost the same setup to reason about speakers and listeners communicating with words, if we assume that sentences have literal meanings, which anchor sentences to possible worlds. We assume for simplicity that the meaning of sentences are truth-functional: that each sentence corresponds to a function from states of the world to true/false.

As above, the speaker chooses what to say in order to lead the listener to infer the correct state:

(define (speaker state)

(query

(define words (sentence-prior))

words

(equal? state (listener words))))The listener does an inference of the state of the world given that the speaker chose to say what they did:

(define (listener words)

(query

(define state (state-prior))

state

(equal? words (speaker state))))However this suffers from two flaws: the recursion never halts, and the literal meaning has not been used. We slightly modify the listener function such that the listener either assumes that the literal meaning of the sentence is true, or figures out what the speaker must have meant given that they chose to say what they said:

(define (listener words)

(query

(define state (state-prior))

state

(if (flip literal-prob)

(words state)

(equal? words (speaker state)))))Here the probability literal-prob controls the expected depth of recursion. Another ways to bound the depth of recursion is with an explicit depth argument (which is decremented on each recursion).

We have used a standard, truth-functional, formulation for the meaning of a sentence: each sentence specifies a (deterministic) predicate on world states. Thus the literal meaning of a sentence specifies the worlds in which the sentence is satisfied. That is the literal meaning of a sentence is the sort of thing one can condition on, transforming a prior over worlds into a posterior. Here’s another way of motivating this view: meanings are belief update operations, and since the right way to update beliefs coded as distributions is conditioning, meanings are conditioning statements. Of course, the deterministic predicates can be immediately (without changing any other code) relaxed to probabilistic truth functions, that assign a probability to each world. This might be useful if we want to allow exceptions.

Example: Scalar Implicature

Let us imagine a situation in which there are three plants which may or may not have sprouted. We imagine that there are three sentences that the speaker could say, “All of the plants have sprouted”, “Some of the plants have sprouted”, or “None of the plants have sprouted”. For simplicity we represent the worlds by the number of sprouted plants (0, 1, 2, or 3) and take a uniform prior over worlds. Using the above representation for communicating with words (with an explicit depth argument):

(define (state-prior) (uniform-draw '(0 1 2 3)))

(define (sentence-prior) (uniform-draw (list all-sprouted some-sprouted none-sprouted)))

(define (all-sprouted state) (= 3 state))

(define (some-sprouted state) (< 0 state))

(define (none-sprouted state) (= 0 state))

(define (speaker state depth)

(rejection-query

(define words (sentence-prior))

words

(equal? state (listener words depth))))

(define (listener words depth)

(rejection-query

(define state (state-prior))

state

(if (= depth 0)

(words state)

(equal? words (speaker state (- depth 1))))))

(define depth 1)

(hist (repeat 300 (lambda () (listener some-sprouted depth))))We see that if the listener hears “some” the probability of three out of three is low, even though the basic meaning of “some” is equally consistent with 3/3, 1/3, and 2/3. This is called the “some but not all” implicature.

Planning

Single step, goal-based decision problem.

(define (choose-action goal? transition state)

(rejection-query

(define action (action-prior))

action

(goal? (transition state action))))

(define (action-prior) (uniform-draw '(a b)))

(define (vending-machine state action)

(case action

(('a) 'bagel)

(('b) 'cookie)

(else 'nothing)))

(define (have-cookie? object) (equal? object 'cookie))

(choose-action have-cookie? vending-machine 'state)Single step, utility-based decision problem.

;;;fold:

(define (iota count start step)

(if (equal? count 0)

'()

(pair start (iota (- count 1) (+ start step) step))))

(define (sample-discrete weights) (multinomial (iota (length weights) 0 1) weights))

;;;

(define (match utility)

(sample-discrete (normalize utility)))

(define (softmax utility b)

(sample-discrete (normalize (map (lambda (x) (exp (* b x))) utility))))

(define (normalize lst)

(let ((lst-sum (sum lst)))

(map (lambda (x) (/ x lst-sum)) lst)))

(define utility-function '(1 2 3 4 5))

(define b 1)

(hist (repeat 1000 (lambda () (match utility-function))) "matching")

(hist (repeat 1000 (lambda () (softmax utility-function 1))) "softmax")Multi-step, suboptimal planning as inference

;;;fold:

(define (last l)

(cond ((null? (rest l)) (first l))

(else (last (rest l)))))

;;;

; states have format (pair world-state agent-position)

(define (sample-action trans start-state goal? ending)

(rejection-query

(define first-action (action-prior))

(define state-action-seq (rollout trans (pair start-state first-action) ending))

state-action-seq

(goal? state-action-seq)))

;; input and output are state-action pairs so we can run rollout

(define (transition state-action)

(pair (forward-model state-action) (action-prior)))

;; modified version of unfold from paper, renamed rollout

(define (rollout next init end)

(if (end init)

(list init)

(append (list init) (rollout next (next init) end))))

;; red-light green-light example

(define cheat-det .9)

(define (forward-model state-action)

(pair

(if (flip 0.5) 'red-light 'green-light)

(let ((light (first (first state-action)))

(position (rest (first state-action)))

(action (rest state-action)))

(if (eq? action 'go)

(if (and (eq? light 'red-light)

(flip cheat-det))

0

(+ position 1))

position))))

(define discount .95)

(define (ending? symbol) (flip (- 1 discount)))

(define goal-pos 5)

(define (goal-function state-action-seq)

(> (rest (first (last state-action-seq))) goal-pos))

(define (action-prior) (if (flip 0.5) 'go 'stop))

;; testing

(sample-action transition (pair 'green-light 1) goal-function ending?)Exercises

Tricky Agents. What would happen if Sally knew you were watching her and wanted to deceive you?

- Complete the code below so that choose-action chooses a misdirection if Sally is deceptive. Then describe and show what happens if you knew Sally was deceptive and chose action “b”.

(define (choose-action goal? transition state deceive) (rejection-query (define action (action-prior)) action ;;; add condition statement here ... )) (define (action-prior) (uniform-draw '(a b c))) (define (vending-machine state action) (case action (('a) (multinomial '(bagel cookie doughnut) '(0.8 0.1 0.1))) (('b) (multinomial '(bagel cookie doughnut) '(0.1 0.8 0.1))) (('c) (multinomial '(bagel cookie doughnut) '(0.1 0.1 0.8))) (else 'nothing))) (define (sample) (rejection-query (define deceive (flip .5)) (define goal-food (uniform-draw '(bagel cookie doughnut))) (define goal? (lambda (outcome) (equal? outcome goal-food))) (define (sally-choice) (choose-action goal? vending-machine 'state deceive)) goal-food ;;; add condition statement here ... )) (hist (repeat 100 sample) "Sally's goal")- What happens if you don’t know Sally is deceptive and she chooses “b” and then “b”. What if she chooses “a” and then “b.” Show the models and describe the difference in behavior. Is she deceptive in each case?

Monty Hall. Here, we will use the tools of Bayesian inference to explore a classic statistical puzzle – the Monty Hall problem. Here is one statement of the problem:

Alice is on a game show and she’s given the choice of three doors. Behind one door is a car; behind the others, goats. She picks door 1. The host, Monty, knows what’s behind the doors and opens another door, say No. 3, revealing a goat. He then asks Alice if she wants to switch doors. Should she switch?

Intuitively, it may seem like switching doesn’t matter. However, the canonical solution is that you should switch doors. We’ll explore (a) the intuition that switching doesn’t matter, (b) the canonical solution, and more. This is the starter code you’ll be working with:

(define (remove lst bad-items) ;; remove bad items from a list (if (null? lst) lst (let ((kar (first lst))) (if (member kar bad-items) (remove (rest lst) bad-items) (pair kar (remove (rest lst) bad-items)) )))) (define doors (list 1 2 3)) ;;;; monty-random ; (define (monty-random alice-door prize-door) ; (enumeration-query ; ..defines.. ; ..query.. ; ..condition.. ; )) ;;;; monty-avoid-both ; (define (monty-avoid-both alice-door prize-door) ; (enumeration-query ; ..defines.. ; ..query.. ; ..condition.. ; )) ;;;; monty-avoid-alice ; (define (monty-avoid-alice alice-door prize-door) ; (enumeration-query ; ..defines.. ; ..query.. ; ..condition.. ; )) ;;;; monty-avoid-prize ; (define (monty-avoid-prize alice-door prize-door) ; (enumeration-query ; ..defines.. ; ..query.. ; ..condition.. ; )) (enumeration-query (define alice-door ...) (define prize-door ...) ;; we'll be testing multiple possible montys ;; let's use "monty-function" as an alias for whichever one we're testing (define monty-function monty-random) (define monty-door ;; get the result of whichever enumeration-query we're asking about ;; this will be a list of the form ((x1 x2 ... xn) (p1 p2 ... pn)) ;; we then (apply multinomial ) on this list to sample from that distribution (apply multinomial (monty-function alice-door prize-door))) ;; query ;; what information could tell us whether we should switch? ... ;; condition ;; look at the problem description - what evidence do we have? ... )Whether you should switch depends crucially on how you believe Monty chooses doors to pick. First, write the model such that the host randomly picks doors (for this, fill in

monty-random). In this setting, should Alice switch? Or does it not matter? Hint: it is useful to condition on the exact doors that we discussed in the problem description.Now, fill in

monty-avoid-both(make sure you switch your(define monty-function ...)alias to usemonty-avoid-both). Here, Monty randomly picks a door that is neither the prize door nor Alice’s door. For both-avoiding Monty, you’ll find that Alice should switch. This is unintuitive – we know that Monty picked door 3, so why should the process he used to arrive at this choice matter? By hand, compute the probability table for \[P(\text{Prize } \mid \text{Alice picks door 1}, \text{Monty picks door 3}, \text{Door 3 is not the prize})\] under bothmonty-randomandmonty-avoid-both. Your tables should look like:Alice’s door Prize door Monty’s Door P(Alice, Prize, Monty) 1 1 1 … 1 1 2 … … … … … Using these tables, explain why Alice should switch for both-avoiding Monty but why switching doesn’t matter for random Monty. Hint: you will want to compare particular rows of these tables.

Fill in

monty-avoid-alice. Here, Monty randomly picks a door that is simply not Alice’s door. Should Alice switch here?Fill in

monty-avoid-prize. Here, Monty randomly picks a door that is simply not the prize door. Should Alice switch here?An interesting cognitive question is: why do we have the initial intuition that switching shouldn’t matter? Given your explorations, propose an answer.

References

Baker:2009tiBaker, C. L., Saxe, R., & Tenenbaum, J. B. (2009). Action understanding as inverse planning. Cognition, 113(3), 329–349.

Dennett, D. C. (1989). The Intentional Stance. MIT Press.

Goodman:2009uyGoodman, N. D., Baker, C. L., & Tenenbaum, J. B. (2009). Cause and intent: Social reasoning in causal learning. Proceedings of the 31st Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society.

Kushnir:2010wxKushnir, T., Xu, F., & Wellman, H. M. (2010). Young Children Use Statistical Sampling to Infer the Preferences of Other People. Psychological Science, 21(8), 1134–1140.

Shafto:2012byShafto, P., Goodman, N. D., & Frank, M. C. (2012). Learning From Others: The Consequences of Psychological Reasoning for Human Learning. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 7(4), 341–351.